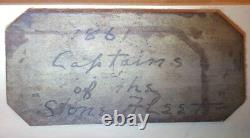

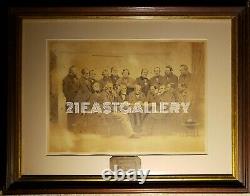

CIVIL War Captains Of The Stone Fleet Whaling Ships New Bedford Ma Charleston Sc

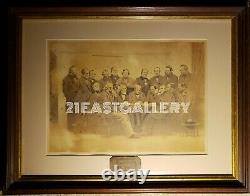

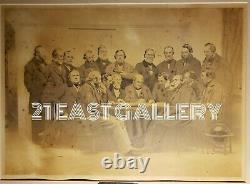

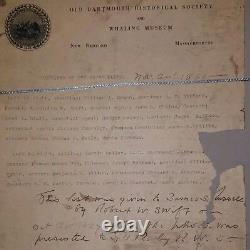

An original photograph by the Bierstadt Brothers measuring approximately 11 x 15 1/2 inches behind its original glass and frame measuring approximately 19 x 24 1/4 inches. Please see a related article and wiki below; many others appear online.

(/Mystic Seaport) DAVID DRURY, Special to the CourantThe Hartford Courant In November 1861, New London residents watched with curiosity as teams of oxen hauled wagons loaded with fieldstones through their streets. The stones had been collected from the foundations of farms and old pasture walls in Waterford and surrounding towns. Generations of farmers had used those walls to keep their cattle and livestock from wandering off.

Now those stones were to provide a different kind of barrier. Their wooden hulls used to carry blubber and oil from whales, but those days had passed with the advent of steam propulsion and petroleum. Holes were drilled below the water lines in each hull. Plugs were then inserted, to be removed when the aged fleet reached its destination: the harbor of Charleston, S. Seat of the Southern rebellion. The industry-poor South depended on its South Atlantic and Gulf ports to import the weapons, munitions, shoes, clothing and other goods from Europe that it needed to wage the war that had begun seven months before. Devised by Army General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, the Anaconda Plan aimed to use the North's superior naval and material resources to squeeze the life out of the rebellion by seizing the Mississippi River, cutting the Confederacy in two, and blockading the 3,500-mile Southern coastland. Twelve others left New Bedford and Boston. The 25 vessels, mostly whalers, were the first of two such fleets that set sail late in the war's first year to toughen the Union blockade and assist in ongoing operations against Confederate coastal defenses. Just one week before, on Nov. 14, a Union flotilla had seized Port Royal Sound, near the Georgia-South Carolina border. Two Connecticut regiments - the 6th and 7th - had stormed ashore to occupy Port Royal's defenses: Fort Walker on Hilton Head Island and Fort Beauregard, both silenced by naval bombardment. It was a notable success in an otherwise lackluster first year of the war for the North. Connecticut and the Navy From the earliest days of the Civil War, strategists in the Lincoln administration realized that for the Union to prevail, the Federal Navy had to play a critical role. The blockade had to choke off the South's supply lifeline. Union warships and gunboats had to seize Confederate ports and move large bodies of troops and supplies along coastlines and inland waterways, particularly the Mississippi and Ohio rivers and their various tributaries.Charged with overseeing the effort was Glastonbury native and former Hartford Times editor Gideon Welles, President Lincoln's gruff, hard-working secretary of the navy. Connecticut, with its long maritime history and established shipyards, became a key supplier, the historic whaling ports of Mystic and New London at the forefront.

In 1861, Mystic had three major shipbuilders and several smaller one. It emerged as a leading center for wartime naval construction.

Steamship construction led the way. The 56 steamships built in Mystic represented, 5 percent of the nation's total, more than Massachusetts and Maine combined. An additional 36 wooden vessels of various size and type were also built. The boom in shipbuilding spawned the growth and development of local subcontractors and suppliers such as the Mystic Iron Works, which in 1862 began fabricating steam boilers and the iron plating the Navy was demanding by late 1861. The iron-clad age had dawned that summer when Confederate naval engineers successfully transformed the burned, wooden hulk of the USS Merrimack into a fearsome, iron-plated commerce raider, the CCS Virginia. Bushnell realized that the Monitor design - a cheesebox on a raft'' with its innovative, rotating gun turret - was superior to his own and lobbied for its selection. In March 1862, the Monitor fought the Virginia to a draw at the Battle of Hampton Roads, ending a serious threat to the Union blockade and signaling the dawn of the modern naval age. Bushnell's own ironclad, the screw-steamer USS Galena, was built in Mystic in just 90 days. Launched in February 1862, it became the Navy's second ironclad and went into action three month later on the James River outside Richmond. Sunken Whalers A directive from Welles in October 1861 set in motion preparations for the Stone Fleet. A New London businessman, 35-year-old Richard H. Chappell, was charged with finding and outfitting the needed vessels. Chappell had made his mark in New London's whaling industry. In just a few weeks time, 45 vessels, mostly old whalers, were acquired from New York City and various New England ports, with 11 of them coming from New London and others from Mystic. 20, 1861 provoking an immediate outcry from the press in South Carolina and across the Atlantic. Shall We Have War With England?' headlined a Hartford Daily Courant editorial on Jan.The editorialist argued that Great Britain viewed the American rebellion as an opportunity to weaken a growing commercial power and would seize upon any pretext'' to tweak the U. The hostile English press itself is already protesting against such a mode of blockade as injurious to the rights of nations. The second stone fleet sailed December 11.

Vessels were sunk off Charleston and Tybee Island, at the mouth of the Savannah River, in early 1862. By then, reports had emerged that that this novel effort to impede Southern blockade-running had achieved, at best, mixed results. The Chronicle says the captain brings a report which will somewhat astonish all of us who have fancied that the stone fleet had closed up from navigation the inlets where the hulks have been sunk. The enterprise is pronounced so far a failure that it is still quite an easy matter to sail or steam into or out of the passage in which the stone vessels are placed! They are sunk so far apart that it is easy to steer between them, and some of them lie in such deep soundings that there are six or eight fathoms of water between their rails and the surface.

" Herman Melville, the great chronicler of the whaling era, mourned what he viewed as a wasteful failure in his poem, "The Stone Fleet. " Here are the final stanzas: "To scuttle them - a pirate deed - Sack them, and dismast; They sunk so low, they died so hard But gurgling dropped at last Their ghosts in gales repeat Woe's us, Stone Fleet! The waters pass- Currents will have their way; Nature is nobody's ally;'tis well; The harbor is bettered - will stay. A failure and complete, Was your Old Stone Fleet. They were to be deliberately sunk at the entrance of Charleston Harbor, South Carolina in the hope of obstructing blockade runners, then supplying Confederate interests. Although some sank along the way and others were sunk near Tybee Island, Georgia, to serve as breakwaters, wharves for the landing of Union troops, the majority were divided into two lesser fleets.Sunk as an obstruction at Charleston, South Carolina, on 19 or 20 December 1861. Laden with 300 tons of stone she was sunk in the main channel off Charleston, South Carolina on 20 December 1861.

Sunk at the entrance to Charleston Harbor on 20 December 1861. [4] Captained by William North. Reportedly she was not sunk and was in service with the US Army as late as 8 January 1862.[6][7]Cossack was a 254-ton bark beached on Tybee Island, Georgia, to act as a wharf for the landing of troops on 8 December 1861. Chappell on 19 October 1861. There is evidence she was transferred to the US Army and was still afloat as late as 8 January 1862.

[5] French had been elected leader of the fleet by his fellow captains and went by the title "Commodore of the stone fleet". Sunk on 19 or 20 December 1861. [10][11]Harvest, was a whaleship that operated out of New England. She arrived off Savannah, Georgia, on 4 December.

Records state that she was retained for use as a coal scow. [6][12]Herald was a 274-ton whaleship active in the Pacific. Her home port was New Bedford, Massachusetts, owner and master George H. She departed 20 November and arrived Port Royal, South Carolina by 17 December. She was presumably sunk in the main channel leading into Charleston Harbor on 21 December, about four miles south-southeast of Fort Sumter and three miles east-southeast of the light on Morris Island.

Richmond, was a 341-ton whaleship that began service in Pacific in 1834. She was sunk along with 15 other vessels on 20 December, about four miles south-southeast of Fort Sumter and three miles east-southeast of the light on Morris Island. [14][16]Leonidas, was originally built as a whaling bark of 231 tons, 320 feet long.

It was active in the Pacific Ocean in 1849, captained by Captain Swift of New Bedford, Massachusetts. From 1850 to 1854, it was partially owned, and captained by, Benjamin Smith Clark, Jr.It sailed from New Bedford in charge of Master John Howland on 20 November. Exactly one month later, it was intentionally sunk, along with 15 other vessels, about four miles south-southeast of Fort Sumter and three miles east-southeast of the light on Morris Island. It ran aground and bilged near Tybee Island in December 1861.

She was 101 feet in length, 26 feet 2 inches in breadth, 13 feet 1 inch in depth of hull, with two decks, three masts, a square stern, no galleries and a billet head. It was sunk, along with 15 other vessels about four miles south-southeast of Fort Sumter and three miles east-southeast of the light on Morris Island. Phoenix, a whaleship of 404 tons, sunk as a breakwater for Union troops invading Tybee Island in December 1861. Rebecca Sims was acquired by the Navy at Fairhaven, Massachusetts, on 21 October 1861, stripped of all unnecessary equipment, filled with stone, and, under the command of her previous master, James M. [24]Robin Hood, East Indiaman (trading vessel), 395 tons, 400 feet. Sunk in the main channel of Charleston, South Carolina, in December 1861. She was beached with Peter Demill and Cossack on 8 December 1861 to serve as a wharf during the landing of troops at Tybee Island, Georgia, at the mouth of the Savannah River. [27]Tenedos (bark), 245 tons, 300 feet, mentioned in Melville's poem.Sisson she was loaded with blocks of granite from New England and sailed on 20 November 1861. She was sunk 20 January 1862 in Maffitt's Channel in Charleston harbor. A woman named Margaret Scott had been executed in 1692 as one of the Salem Witches. Mentioned in Melville's poem as the Lee. This item is in the category "Collectibles\Militaria\Civil War (1861-65)\Original Period Items\Photographs".

The seller is "theprimitivefold" and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped worldwide.